This essay cost me more than time and ink and some five years to write after the death of my son, Benjamin Hammerschlag, at age 46 on November 4, 2017.

Lifeboat

After my forty-six-year-old son died, I needed to go back to school. Not to stand at the red door of the schoolhouse with hope, but to learn how to survive.

So, I took notes like a child.

Note #1: I’m not going to write about God. The worst sentence I heard after my son died was “God needed him more than you did.”

Note #2: He shot star-like in his world and that star fell to the ground, shattered, where he lies now in Bellingham, WA, where I buried him.

Note #3: His death brought me to my knees. Every time I thought I could get up, I saw his body clothed in a non-Jewish funeral home on a gurney. His plaid flannel sport shirt, his blue jeans. They dressed him, something we Jews do not do. I expected to see him in a shroud with his head on a marble pedestal, the way I saw my mother for the last time. But there he was, dressed as if ready to hike or do chores or sit at his laptop that I now have.

Note #4: I’m turned inside out like a sweater. The raw of me laid bare for everyone to see. Never good at hiding. I often tried. He’d say, “You’re a lousy poker player.” —because whenever I got a flush or four of a kind or a straight, the luck showed in a blush on my skin. Now I’m anything but straight. I’m a crooked line.

Note #5: The raw threads, the tied knots from the sweater I might’ve knitted are now on the outside. It doesn’t matter what clothes I put on, how lovely the long black jacket I wear flows. The raw knots of the sweater where the end stitch is tied off to begin another row—to knit, purl, knit—show. I have no good side anymore.

Note #6: The gravel road to my son’s house on his vineyard raises dust that covers the windshield. A sign says, Go Slow. Keep Dust Down. When I went there to memorialize his life, I closed the window but the air is in me now. The perfume of a dusty road that led to the home he built on the hill above his vineyard, where he grew the grapes, made the wine, walked the narrow, manicured paths between the vines, tasted the grapes. His land with fruit trees, pears and figs. And his “dream tree”: Under it he placed his wooden table and chairs. He surveyed the land he owned and cared for, loved, that he left to his sister after he made her promise never to sell it. An unfair promise. Oz so far away. She asked me before she sold it, “Will he haunt me?” I said, “We don’t believe in such things. You know that. Do what you need to do, my love.”

Note #7: He haunts me like the long retired Red Hen railroad cars he’d rescued and placed one next to the house, one down among the vines—for storage. I store him and he haunts me like a gravel road that raises dust and memory.

Note #8: He haunts me like fire, a fire like no other: blue fire, black fire, green fire, white fire and I am the ash, scorched and burned. The day I got out of the car after grocery shopping, let him out, the two-year-old—then gone. We all looked, scoured the neighborhood. I went to the old mansion behind our house—the land that surrounded it was for the housing development where we lived— and I found him there. He was swinging on an ancient swing set. I see a fire now beneath that swing set. And in the ash, he and I lie. He, the child-man who burns with me in the ash of stay, the way he stayed in my womb for twenty-two hours of labor, the way he would not come into this world. That is where we are. We are in the womb and the fire burns us both and we are ash, the ash of stay—and gone.

Note #9: I ask this question: Is the desert a dusty memory, not a place?

Note #10: I wrote a book that closes with a story that begins, “There once was a woman with three hundred and twenty-seven cookbooks who never cooked.” Recipes chronicle the losses of my mother, my sister, my father. The story opens with the Talmudic quandary: Two men are in the desert. Only one of them has water. If the one who has the water shares it, both will die. If he drinks all the water, one will live. The woman remembers this question: What should he do? The story closes after all have died and she’s figured out what was missing from the recipe for a lemon meringue pie that failed so many times it had become a joke in her family. At the story’s end, the woman, who is me, figures out what was missing from the recipe. She says, “I did not know what I deserved or what was just. But I knew I would make the pie, that it would be hard to make and that it would be my favorite.”

Note #11: I am in the desert. The search for water, constant like my tears that flow unbidden and unforgiving. They come like the tide without an ocean. I see the paradox and I live inside it. My son, like me, was drawn to the water and never lived far from it. In Australia, he lived on his vineyard with an apex where he sat and could see the ocean. He kept the sea always in his view even when he didn’t dare venture into it for fear of sharks.

Note #12: My grief is like the ocean and here is what she says: “I stand on a wave above you. You see me. You hear me. You want me. But when I call to you, you don’t think I know you, see you, hear you, want you, but I do. Maybe even more than you want me. I am dressed in a chiffon dress that mirrors the sea your son loved. So it is not sky blue, it is green-blue, some days as green as his eyes that were so sad, that saw what was coming, that couldn’t overcome but tried.”

Note #13: Unlucky number? We don’t believe in such things.

Note # 14: He used to say—he, so far away in Oz, “You want to be ‘beamed like Scotty’” and then he flew me there, first class. When the ticket was on its way, he said, “Don’t look at what I paid. You’re my mother. I beam you.”

Note #15: The ocean I flew over speaks again: “I pull you with the flow of my long black hair in an ocean of wind and though you think I pull you into the sea, that you will drown, you will float on the chiffon of my dress as the waves crest and fall and you will rise like the sun that you’ve seen behind my form. You will rise.”

Note #16: He would say to me, “I will take care of you. I will take care of everyone.” He said this as a boast, but he knew some things he would leave behind I did not know about—an insurance policy with me the only beneficiary. As if that would help? I still dream him every night, wish him back. Need him.

Note #17: I’ve learned my heart is a lake where something has fallen, a splash appears and stays. Fronds of water rise around what has fallen. The splash instead of a return to surface calm stays, open and splayed. That open water with risen water all around the fallen place is an open hand and palm that takes in the wounded and the lost: You, my son, my love, are in that splayed and open space. Did you know that with your loss, my heart has opened and deepened and that the place for falling remains, the falling of the fallen, the falling of the hurt? The space remains ready and waiting for any to enter. You made that place for me. An open heart that will not close, an opening whose surface is broken but not fractured. The fronds of water around the fallen are clear grey-blue. Light shines through. In the opening, you see a soft place to fall, a safe place to fall, a place that catches you, surrounds you with the waters of my tears and the water of all the seas you loved. It is a call. It is an answer. “Come,” my heart says, “Come.”

Note #18: This morning I woke to a dream: I say to someone, “I need to call him to see how he is.” I dial his cell and someone at the apartment building where he once had a condo in the West Village answered: I could hear his voice in the background.

Note #19: He echoes in my heart.

Note #20: I face the unknown the way he did. He calls to me and here is what he says: “Here is what I see. I see you, my mother, my cherished one, alone. I know you feel abandoned even though you know I’d never have left you if I could have stayed. I see you in fire and sky. I see you in the fires you wrote about: Blue fire, green fire, white fire and chariots of fire that rise up on the clouds and ride on the sunrise, yes, the one you saw this very morning. The sky streaked among gray clouds, fire on the mountain, above the mountain. I heard you say, ‘Do you see that?’ Do you know that in that fire-sky, I saw you. I know you believe you’re not seen, that you write this in darkness. I see you from the beyond you doubt. I am not in the grave that haunts your dreams. I’m in my own dreams and my own ineffable real. I ride that used Porsche 911 that I searched for in my fifteenth year after I’d saved every cent I’d earned from all the jobs I’d held from age twelve on. So, my love, my mother who saw me every day I was alive, think of me in fast cars that fly on fires in the sky and know that you are seen.”

Note #21: I woke up one day thinking, Today is day twenty. Or on another day, Is it day thirty or forty? And then, Is it four years—or is it five? Any number now reminds me of those early days, weeks, months when I counted each day as it passed. I remember thinking three weeks had been so long. I don’t remember when I stopped counting. I remember when I realized I had. Like so many things, I worried this forgetting meant I was ‘getting over’ his death. If everything else would fade, too. If I was somehow not holding on hard enough, as though the passage of time were under my control. The truth is: some things have faded. But the missing remains.

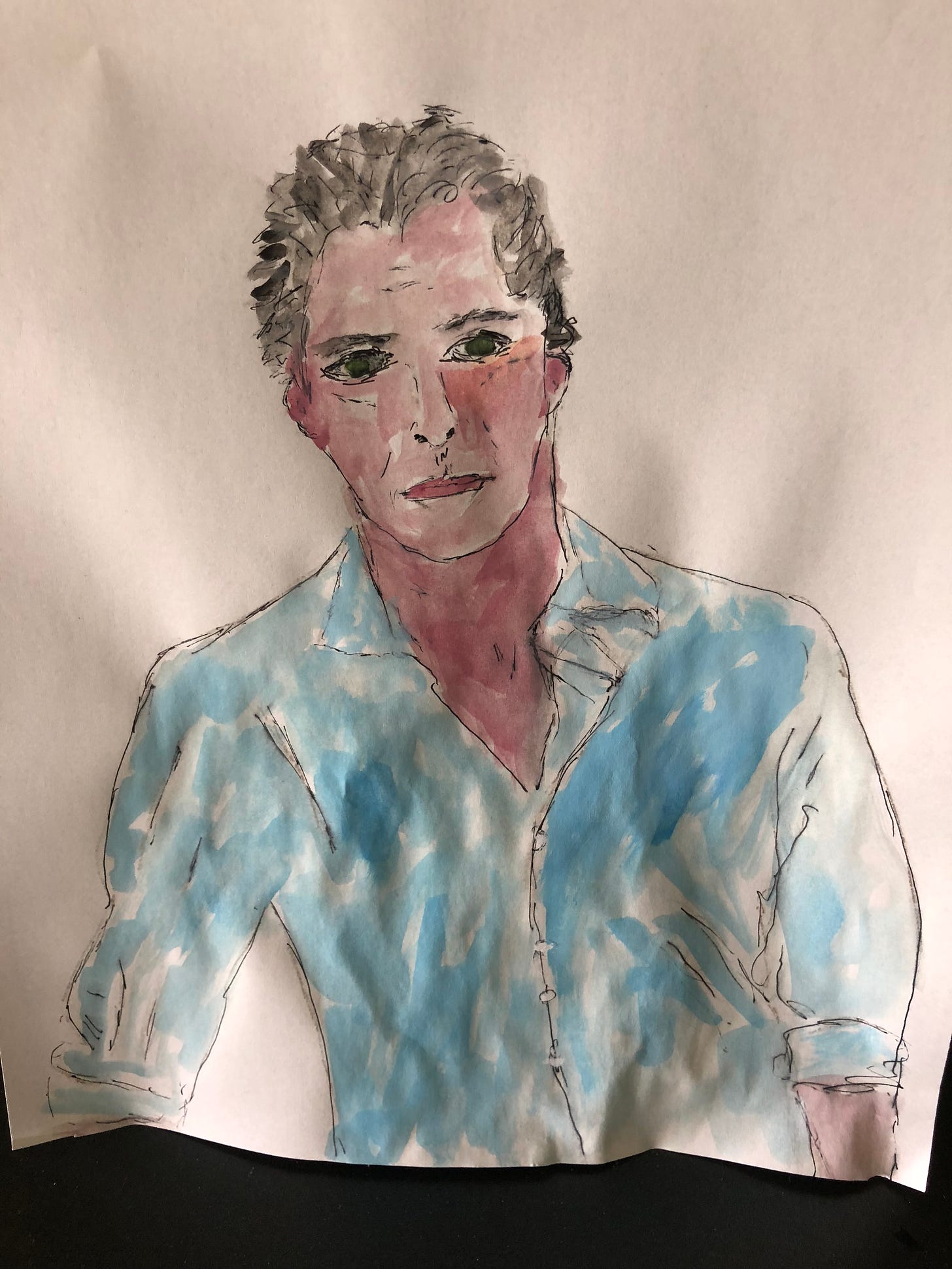

Note #22: After he died, I stopped painting except for the day on his land where I held the memorial: The watercolor of him I did on A2 paper, crinkled and marred by the lack of a correct surface. I’ve learned the right surface matters—but, for this passage through, no firm ground holds. Instead, the spiked surround of loneliness pervades my life.

I’m carried on the surge of the ocean under sky that rains into the sea of loss. I know that others too may be lost and searching through an unknown passage, that others too may have felt as if they were drowning, that they too have been without a lifeboat. To them, I say: Comfort can abide not-knowing and that you, who read this, are the lifeboat in my ocean.

Love,

Mom